Consolidations among gold miners p. 1

In the past we didn’t have many opportunities to discuss subject of gold miners on Metal Market Europe blog. We’d like to address this matter, as since couple years we witness strong trend on great sectoral mergers and acquisitions. Some could be even considered as tectonic in size, as relating to biggest names in industry.

Why gold miners joined their efforts in the past?

We just recently left 1st half of 2022 behind us, but one thing already could be said with 100% certainty – we experience highest value in the last 10 years on number of mergers and acquisitions in mining sector (overall, not only gold mining). Pending and completed deals are currently at 65 bln USD for 2023 alone. Of course, data without something to compare it to is meaningless. In rather calm decade of 1990-2000, total value on sectoral mergers and acquisitions was at 27 bln USD. But from 2000 to 2010 mining sector saw strong trend, of over 1000 acquisitions on combined value of 121 bln USD.

Focusing however on yellow metal - gold price was growing basically since 2000 to 2012 and remained high in terms of price until beginnings of 2013. Rapidly raising prices were considered as main reason to support big moves in mining sector. To the point, that in between 2007-2012 sector started to behave like eventual drop in price would be something impossible. During that period, it became nearly common for miners to try to deliver as much gold as possible in attempt to maximise volume related profits and to hold the crown of prime gold miner worldwide. Biggest sectoral names at a time - Barrick, Goldcorp, Newmont, and Newcrest - were basically in a constant race.

However gold rush was making miners less careful with regards to cost control. In many cases they preferred to maximize volumes, irrespectively to extraction costs to be occurred in a short and mid-term. Apart of being project heavily invested, giants were also heavily acquiring junior and mid-size miners. Often it was happening with approach ‘no matter the cost’ – as gold was growing in price terms and was supposed to continue longterm. Just to mention two instances - Goldcorp buying Canplats in 2009 for 229 mln USD or Newcrest acquiring Lihir in 2010 for 8.5 bln USD - both deals were made with approx. 40% high premiums.

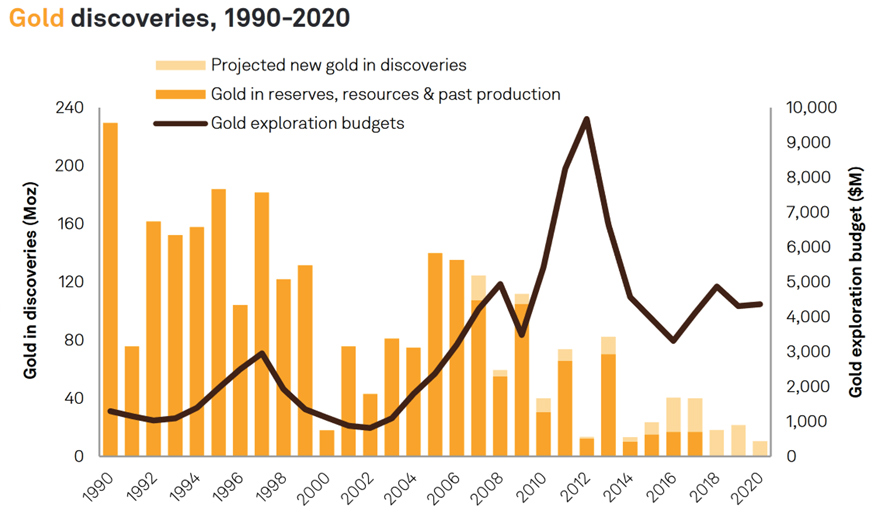

Exploration budgets and gold discoveries 1990-2020, compiled by S&P Global. Source: World Exploration Trends 2022, PDAC Special Edition

Comparison of 2000 and 2012 reports made by McKinsey show, that annual capital expenditures by gold mining companies increased 10-fold in compared years, with aggregate spend exceeding 125 bln USD. However, about two thirds of projects exceeded budgets by 60%, and half experienced delays of one to three years. On that last two figures we need to be clear - it is nothing unusual for large projects or multibillion so-called megaprojects to exceed initially assumed cost and time thresholds. Problem appears when capital heavy investments had been done, and suddenly investors realise that expected profits are unreachable in assumed timing, or investment environment had changed drastically. And that is what exactly happened with beginnings of 2013, when sudden crash in price of gold caught many miners unprepared for such and capital heavily engaged. As a result, period of 2013 to beginnings of 2d half of 2019, was unsupportive to heavy mining expansion due to relatively low price of gold. This status started to change with beginnings of 205 when miners improved their profitability, however they still lagged significantly to equities i.e. from S&P. As a result, sectoral financial condition was significantly improved i.e. comparing 2013 and 2019, however still lagged in comparison to “golden period” 2010-2012.

Additionally, in the years preceding Covid outbreak, many institutional investors lost interest in mining entities. Most of the reasons lied in structural changes in financial markets. Changes in macro-economic environment i.e. in form of quantitative easing supporting stocks, cost pressures, capital movement towards ETF and indexed investing and disenchantment with mining sector performance, effected in outflow of certain investment capital from gold mining sector. And that turned to be additional burden affecting sectoral investments, especially experienced by juniors. On the other hand, backed with physical gold ETF sector acted as a kind of airbag in 2020, when, in result of pandemic and lockdowns, demand for gold jewellery fell sharply and temporarily. It was purchases made by ETFs that allowed gold demand to remain relatively stable for a while.

Industry assumed rulebook timings are as follows: Exploration and prospecting – 1 to 10 years. Development of mine including permits and works takes 1 to 5 years but it is nothing unusual to have it extended even to 10 years, especially in case of undercapitalised juniors. Mining operations are usually 10-30 years. Assuming that deposit is rich, this may be extended for another decades. Finally, terrain re-cultivation and decommissioning usually up to 5 years. So, assuming optimistically that we found and had tested deposit, gathered all permits and attempted to build open pit mine – for 1 to 5 (or more) years we have large chunk of capital frozen ours and provided by investors, and we’re being prone to material, labour and energy (plus other overheads) cost fluctuations. Of course, it is still possible to make strategic mis-judgment regards to larger cycle, which could effect in our targeted metal to drop heavily in price. As an effect, our investment, fitted with leased or bought costly equipment wouldn’t be able to meet profitability, but instead had to struggle to remain economically viability.

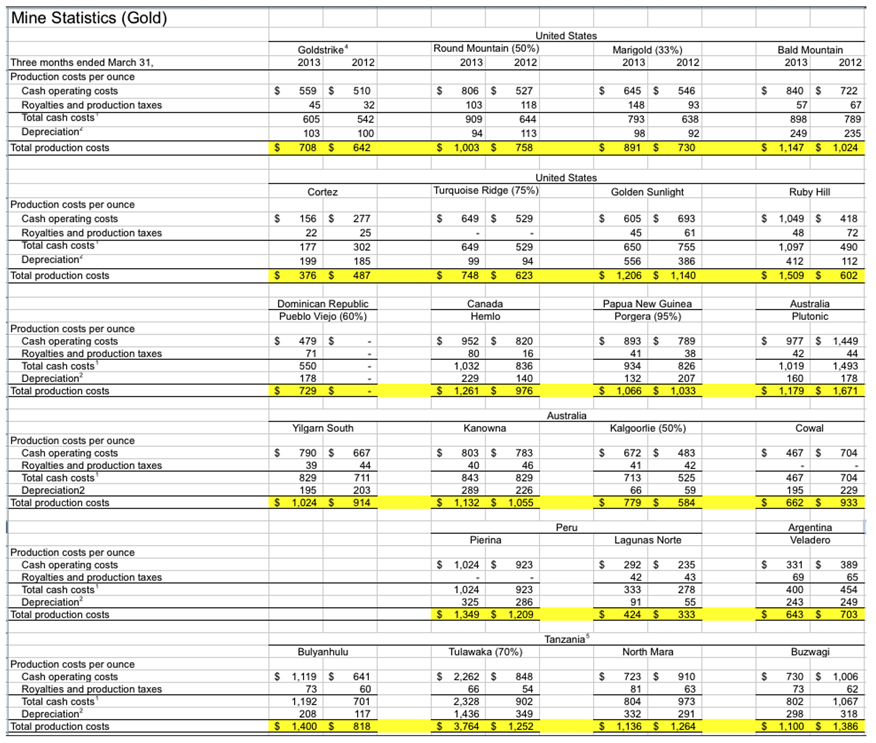

How much and how deeply it may be changed? Table below comes from Barrick Gold and refers to costs of mining 1 ounce of gold from its operations for 2012 and 2013. At that time, releasing such dataset wasn’t usual practice. Gold closed year 2012 on 1674 USD and 2013 at 1205 USD, making some of the mines listed below suddenly appear either below or just above point of financial viability. Of course each of these has to be taken under consideration individually as could’ve been affected by individual factors, like planned reconstruction, natural catastrophe, protests or near-end of lifetime due to extensive deposit extraction.

Comparison of 2012 and 2013 All in sustain costs to produce 1 oz of gold for operations in Barrick Gold portfolio. Gold closed 2012 on 1674 USD, and 2013 at 1205 USD, making some of the above i.e. just above point of viability. Source: https://www.businessinsider.com/the-cost-of-mining-gold-2013-6?IR=T

In 2011 gold hit 1920 USD, remained high for most of the following year, only to wreak havoc on 2013 charts ending year at 1200 USD levels. That required miners to change their approach and execute aggressive cost cuts. Lesson was costly, and made gold industry capital leaner, meaner and smarter. Hence sector in 2023 is not same as decade ago. So logically it applies different approach regards to mergers and acquisitions.

Of course, we are aware that it is not only price of gold that matters. Each end every individual mining operation may experience its own individual problems related to quality of deposits, growing costs and changes on local mining policies or political. Just as example - miner having operations in Burkina Faso may have better quality of deposit and low direct production costs comparing to its other operation in USA. Also with regards to ESG, its African operation will be less cost demanding. However in this case he is forced to spend more on logistics due to quality of local roads and lack of ports in a landlocked country. Additionally he has to spend small fortune on security. That includes drones, professionally equipped security crew, armoured vehicles – all you can imagine is needed to secure investment in politically instable country.

Why gold miners join their efforts now – on sectoral trends

Gold miners worldwide faced prospect of stagnating production volumes since years, as they face harder-to-mine deposits and rising input costs. To prove above, we only need to make a deep dive onto past yearly and quarterly reports of some major miners. In our case we referred to well established giants – Barrick Gold, Newmont, Newcrest and AngloGold Ashanti. That’s being seen as a catalyst for more mergers and acquisitions, as companies seek to boost volumes and improve efficiencies by finding mutual synergies, and that in the safest way, without risk of too large exposition of capital onto newly established mining projects.

First main reason for the above is of course related to exhaustion of deposits located close to earth surface. Times of rich gold veins being exposed by heavy rains (as i.e. was noted in Byzantine chronicles regards to Armenia) are far behind us. Centuries of gold mining caused depletion of such deposits. Additionally, technological progress allowed us to work on and process deposits absolutely beyond point of historical financial viability or simple possibility to be discovered in the past. So, with 100% certainty we could say that vast majority of assumed 208k t. of gold mined trough history ever, has been mined just in the last 50-70 years. With shallowly located deposits being exhausted, miners must face reality of less gold in ore, hence in theory same amount of ‘labour’ as 10 years ago, will result today with lesser output. Just comparison of 2012 – 2019 reserves of largest gold miners shows decline my 32%.

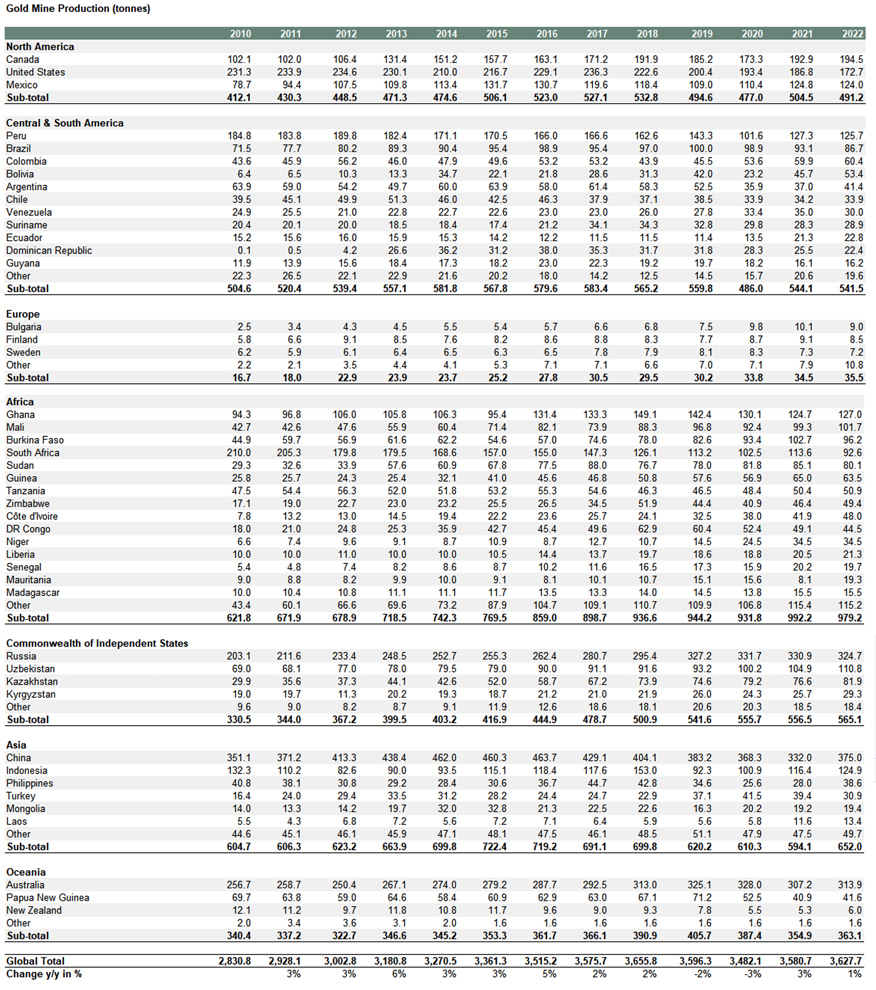

This is the reason for concept of peak gold. Like peak oil, it refers to the point when gold production from prime sources is no longer growing, and even declines in longer trend. Mine supply was growing in recent years by approx. 1%-3% y/y, with trend broken in 2019 and then 2020 – in this case due to Covid caused force majeures and restrictions affecting businesses. Additionally, considering sanctions applied on Russian gold and fact that China has restrictions on exporting its own gold - just that directly affects over 600 making most of this volume unavailable for western customers. Current lack of production growths or even shrining production volumes experienced in different regions of the world, make growing African supply (i.e. from Ghana, Sudan, Mali and Burkina Faso) being even more important now. Hence strong demand must be partially met by secondary resources like processed gold scrap.

Below table is provided by World Gold Council and shows official gold mining volumes for period 2010-2022. North America is in decline, Europe is depleted since medieval times and its volumes do not matter much, Africa has 2nd highest worldwide volumes as a region and since 2010 managed to increase supply by staggering 1/3, even despite troubles affecting South African miners. Former soviet republics remain on similar but high levels since 4 years but managed to grow long-term output by 2/3. Asia and South America deliver high volumes but recover from variety of different issues (protest, riots, post-Covid etc.). Australia and Oceania struggle to deliver more gold, due to major production changes in Grasberg mine.

2022 detailed mine production, division by countries and regions. Source: World Gold Council

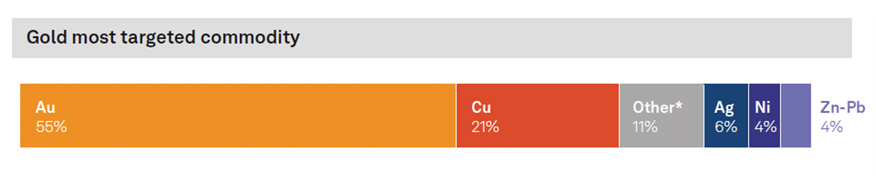

And here comes 2nd reason for stagnation which lies in policies and politics. Years and decades of mining activities on deposits located shallow in earth’s crust made most of them mostly depleted (one of such most notable examples is Witwatersrand in South Africa). Persistently high gold price triggers growth in exploration budgets on global scale. And approx. 50% of these, worthy 6.2 bln USD are dedicated to search for yellow metal. However, this must be looked for deeper which is costly. Not even mention about environmental or local protests. After all, everyone would like to have cheap goods and energy, but no one would like to have deposits being mined in near proximity of his household. US press created in 80’s even appropriate term to describe such approach – ‘not in my back yard’ (NIMBY).

Alternatively miners could consider operating in jurisdictions either politically instable, less miner friendly or authoritarian. But at the same time having better quality deposits. In this case we could say about high risk-profit operations. History shows it is nothing unusual for miner’s assets to be forcibly ceased by protesters, rebels, or local militia. Other case is when political surrounding change and foreign jurisdiction suddenly demands its own piece of cake (Indonesian Government on Grasberg), or whole cake (Newmont’s operations in proximity of Muruntau in Uzbekistan). Recently we had opportunity to analyse this subject in our analysis ‘Mexico’s new mining law may affect silver supply’.

Gold remains main commodity on metal exploration budgets. Source: Source: World Exploration Trends 2022, PDAC Special Edition

Unfortunately, there is no gold meteor going to strike Earth in nearest future. Space mining is currently beyond any points of financial and technological viability. Seabed mining is in development stage but again it requires geological studies. In reality, miners have choice between:

- Mining in potentially dangerous jurisdictions (i.e. Chad, Sudan, Burkina Faso),

- These demanding not be treated as international mining colony and applying nationalistic approach to deposits (i.e. South America or Indonesia),

- Rich in deposits but difficult due to weather conditions, short seasons, and therefore prone to higher equipment wear and tear costs (Alaska),

- And potentially friendly but leaning to be more ‘sustainable’, expensive and with gold deposits mostly depleted or undiscovered (i.e. Canada, USA).

In the above context, we need to remind pre-pandemic words of Mark Bristow – CEO Barrick Gold, who called for strong sectoral consolidation and targeting African gold deposits, due to looming serious reserve crisis.

Current metal (not just gold) exploration budgets have targeted predominantly Central and South America (Latin America) at 24% in last years. At the same time, share of large players on this direction has fallen from 71% in 2017 to 56% in 2021. Further down the line, however, exploration budgets are heading towards certainties, renowned for their legal and political stability, with experience and sufficient number of sectoral specialists, where the only threats may be the growing ESG trend and energy, material and human costs. That is Canada, Australia and the USA.

3rd danger to consider is inflationary environment. It affects operating costs, employee wages and energy costs, which is clearly visible in financial reports of miners, however that is being for now offset by gold prices. Having high inflationary prices, expected by many to persist until end of current decade, discourages investors to make financially heavy investments that may or not bring expected results. Although with growth in price of gold there is a growth of exploration drills, there are no guarantees that potential deposits will be economical to be mined.

And on the final note, need to mention about another dangerous trend, which will backfire in a long-term. As a career choice, mining has seen better times. And it is clearly visible on both metal markets and even more on hydrocarbons. Looking at the 2014 to 2020 period in case of Canada, there is a clear pattern of a decline in total enrolment to mining engineering by 42%. And while this declined, more students were registering for other engineering fields. Additionally developed countries provide array of possibilities in services sector, which do not produce goods themselves but provide personal development and earning opportunities. Internal migrations from rural to urban locations is proof of that. Additionally, perception of work in mining sector is that it is ‘heavy and dirty job’. Lot of that sector owns to media, who forget to mention that now-a-days mining engineering differs from how it looked like in 50’s. And another aspect to consider on this occasion are ‘sustainability’ trends. Young people start to perceive mining only as something environmentally dangerous, forgetting that in a production sequence it is a backbone of industry and main reason why we actually could acquire goods.

We have reasons for extensive mergers and acquisitions – scarcity of gold, investment risks, growth of costs and possible staff shortages. Hence, purchasing low-cost smaller producer – who already developed his operations - is being considered as much better way to expand operation and volumes delivered, especially if miners expect growth in demand or price on metals they produce. When apply this type of approach, market provides extensive choices. According to some preliminary studies for 2019, just on Canadian TSX and TSXV – which are considered mining heavy exchanges – there were over 950 mining / exploration entities, with over 800 of them with market cap below 50 mln USD. Hence vast array for potential acquisition opportunities exist, especially if research would bring us to some underfinanced ‘jewels’ with good results (P/E, EBITDA itp.), and good quality of deposits.

Above factors have to be considered as supportive for mergers and acquisitions, or just to form local joint-ventures to meet certain goals. One of such is Nevada Gold Mines, which we’ll going to discuss later in a text. But considering i.e. geographical proximity of certain operations held under different corporate banners, it is cost wise i.e. to share some facilities. Of course, synergies are to be found on various levels, and should come as no surprise, that formally integrated by acquisition entities, usually make decision on disposing certain acquired underdeveloped or less prospective assets, in attempt to improve its financial books. According to research by McKinsey, even despite the problematic year 2020, gold price increases have enabled miners to improve their liquidity, which is evident even now. Furthermore, it is important to remember that gold mining, due to the growing popularity of its end product, remains sector attractive to capital flows. In addition to the dividends paid to shareholders, it is reasonable to assume that a sizable portion of acquired capital has been directed to secure long-term growth.

However same factors remaining for a long time - current macro environment with strong inflationary pressures and skilled labour shortages - may negatively influence willingness to make great purchases. Miners may therefore be less prone to spent capital, as expected slowness in global economic growth, will affect demand for commodities, along with prices, however it will be rather short term. After all, usually multi-billion deals are being made with long timing in focus.

Trend to make larger entities – and therefore less prone to potential market tumoils - is not to be applicable only to precious metals miners. Just in 2023 and 2022 we witnessed large mergers and acquisitions, just to mention i.e. merger of Allkem and Livent on lithium, acquisition made by BHP on OZ Minerals (predominantly copper) and further takeover attempts made by Rio Tinto. However need to remember, that consolidation always bear risks that TBTF (too big to fall) entities may be created. And they may influence heavily smaller market participants and commodity markets overall.

To be continued…